Chapter 14.4 – Chromosomal theory of inheritance, linkage, and extensions to Mendelian genetics.

OBJECTIVE: Understand that genes are located on chromosomes and the chromosomal basis of Mendel’s laws

- Look at Fig 14.7. What is Mendel’s first law? How does it relate to our chromosomes?

-

What is Mendel’s 2nd law? How does it relate to the arrangement of chromosomes during meiosis?

OBJECTIVE: Recognize the patterns of inheritance associated with sex-linked genes

- Draw the results shown in Fig 14.10:

- Show the mating of a wild-type female fruit fly with a white-eyed male.

- Make sure your Punnett square reflects the gametes that are produced by the parents.

- Show the full-sib mating of the F1s.

- Make sure your Punnett square reflects the gametes that are produced by the parents.

- Show the 4 types of offspring in the F2

- Label each individual with their genotype.

- Show the mating of a wild-type female fruit fly with a white-eyed male.

- Using a different cross, would it be possible to produce a white-eyed female? What cross could produce a white-eyed female?

- What cross would produce:

- half white-eyed females w+w ♀ × wY ♂

- all white-eyed females (all males would also be white-eyed)

- At what stage of meiosis does the X chromosome separate from the Y?

- Hemophilia in humans is X-linked, recessive. Show the four genotypes of children possible from a normal female whose father was hemophilic (figure out the mother’s genotype first!) and a hemophilic man. Use XH and Xh for the dominant and recessive alleles, respectively.Showing the mother’s allele first: XHXH, XhXH,

XHY, XhY -

For the question above, from which parent does the hemophilic son inherit the hemophilia allele? Sons always inherit their X chromosome from their mother

OBJECTIVE: Recognize that recombination results in combinations of traits that are different than those found in either parent

OBJECTIVE: Understand how recombination can affect both linked and unlinked genes.

- Look at the results of the meiosis shown in figure 14.11. Compare the gametes produced with the gametes produced in a standard dihybrid cross such as shown in 14.5(a).

- Based on your answer to the question above, what can you say about the chromosomal location of the traits that Mendel used in his dihybrid crosses?

- What is genetic recombination?

- What are ‘linked genes’?

- How do you know that recombination is occurring despite the genes being located on the same chromosome (Fig 14.12)

- If two genes are located on different chromosomes, what ratio of parental : recombinant offspring do we expect? Why is this the case (think of meiosis). We would expect a 1:1 ratio (ie. 50% would be recombinant). Look at Fig 14.5(a) in your textbook.

- What process allows recombination between genes on the same chromosome?

- Explain why genes that are located far apart on a chromosome are more likely to be recombined than genes located close together. Crossing over is more likely between two genes that are far apart on a chromosome. If two genes are next to each other (or close), then crossing over between them is unlikely, and alleles of the two genes will usually be inherited together. When the genes are distant (but still on the same chromosome), the recombination frequency will reach 50% and they will assort independently, as if they were on separate chromosomes.

Extensions to Mendelian genetics (14.5)

OBJECTIVE: Understand and Describe Extensions of Mendel’s Rules Study the vocabulary: incomplete dominance, codominance, multiple allelism, pleiotropy, epistasis, environmental effects, polygenic inheritance. Make sure you add them to the appropriate explanations above.

- What are “dominant” and “recessive” alleles? Note that to answer this question you must think about the phenotype of heterozygotes, not homozygotes. A dominant allele ‘hides’ a recessive allele so the heterozygote looks like one or the other homozygote. The homozygote that looks like the heterozygote has the dominant alleles.

- What are codominant alleles? Again, think about the phenotype of the heterozygote. Give an example. Think of the MN blood types. Both alleles are expressed in the heterozygote.

- What is incomplete dominance? Again, look at the phenotype of the heterozygote. Give an example. Think of the snapdragons. The heterozygote has a phenotype that is intermediate between the two homozygotes.

- Does each gene affect Just one trait? Explain. Example?No, think of pleiotropy and Marfan syndrome

- Are all traits determined by a gene? Explain. Example?No, many traits have strong (or even exclusive) environmental influence. Also, many traits are determined by more than one gene.

- How does the environment affect phenotypes? Explain. Example?

- Can different genes work together to affect one phenotype? Explain. Example?

- What is meant by a ‘quantitative trait’?

- What do you think would happen to the distribution shown on the left of Fig 14.20 if there were more genes (4, 5, 6, etc.) that affected skin color in the same way?

- The Freeman textbook explanation of gene interactions (comb shape in chickens) is difficult to understand. We will use the following example in class. See also the figure below (please check this reading guide online for a color version of the picture).

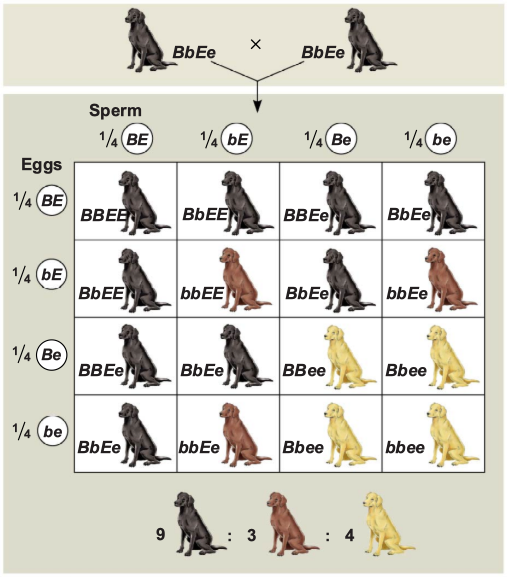

- In labrador retrievers, coat color is determined by 2 genes, B and E.

- The B gene determines the color of the hair shaft, with the dominant allele (BB, Bb genotypes) producing black dogs, and the recessive allele (bb genotype) producing brown dogs.

- The E locus simply determines whether or not any pigment is deposited into the hair shaft. The dominant allele results in pigment being deposited (genotypes EE and Ee). The recessive allele prevents color from being deposited (genotype ee).

- If pigment is deposited, then the dog will be the color of that pigment (either brown or black). If no pigment is deposited, the dog will be ‘yellow’. Note that if the dog is ee (and has no pigment deposited), the genotype at the the B locus doesn’t matter – in all cases it will be ‘yellow’.

- You can see the results of a dihybrid cross in the figure below. All ee dogs are yellow, regardless of the B locus. Calculate the phenotype ratios: you’ll see that this is a modification of the standard 9:3:3:1 ratio that we expect from 2 genes. In this case, one of the groups of 3 has been combined with the double recessive homozygote to form a phenotype ratio of 9:3:4.

- You can see that the two genes interact with each other to produce the final phenotype. There are different ways that genes can interact, and this way is called epistasis. In epistasis, the effects of one gene can be completely masked by the effects of the other gene. Freeman descusses a similar case with the H gene masking the effects of the I gene in the ABO blood type.

- In labrador retrievers, coat color is determined by 2 genes, B and E.

- How are the labs in the figure above a modification of the 9:3:3:1 ratio? Which groups are combined?

- What does the E locus do and why are all recessive homozygotes yellow, regardless of the other (B) locus?